Contents

- Finding science that, and scientists who, have impacted policy

- How to understand how scientists have impacted policy

- TL;DR I’m starting to hone in on whom and how but need better structure for analysis

- References

Weeknotes are my way of reflecting on my readings, research and thoughts from the week. They link and contrast experiences and observations that happen to have occurred in a short period of time. I am writing these notes quickly, doing my best to correctly represent the sources, but I would love to learn if I am mistaken in my understanding in any way. You can contact me on https://climatejustice.social/@PenguinJunk.

I set aside much of the literature reviewing this week to consider more carefully what is my methodology. I have worked on two aspects to this - what and whom am I going to study, specifically, and how I will study them.

Finding science that, and scientists who, have impacted policy

From my very early discussion with Kris De Meyer we talked about learning from scientists who have impacted policy. There are several disciplinary contexts to this. Our initial conversation was around the psychology and behaviour of individuals who are successful garner action using science communication (e.g. De Meyer, Coren, et al., 2020 and De Meyer, Hubble-Rose, et al., 2022). There are aspects of this that also, to my mind, sit well with policy theory, particularly the actions of a policy entrepreneur (Kingdon, 1993) and problem broker (Knagg ̊ard, 2015) from the Multiple Streams Framework. Certainly, these actors have been identified in real policy settings. But in order to learn from such individuals, I need to identify them. I have spent a bit of time both thinking about scientists that appear to have policy impact, and I have even asked Ecosia’s AI assistant, and this results in some high profile individuals, often with positions that directly interact with public policy and decision making. Whilst this is interesting, other individuals may have different perspectives and therefore this week I have spent time trying to identify a more systematic approach to finding scientists who have influenced public policy.

Databases about research

I was initially very excited to learn that the UKRI Gateway to Research appears to have an API endpoint that returns “policy influences”: https://gtr.ukri.org/gtr/api/outcomes/policyinfluences. Unfortunately, I cannot currently get my API calls to work for this and have since learned from the GtR team that the API is having “issues”. I also looked at UKRI Research and Innovation Outputs but nothing here really indicates if public policy has been influenced. The same appears to be true for Research England’s Knowledge Exchange Framework (KEF) which applies to institutions rather than specific research activities. Superficially, in the KEF, the perspective “Working with the public and third sector” would include impacting public policy but it breaks down to contracts and consultancy (“customer pull”), rather than having the opportunity for broader public sector impact including impacting public policy by “knowledge push”.

Digging into the REF 2021

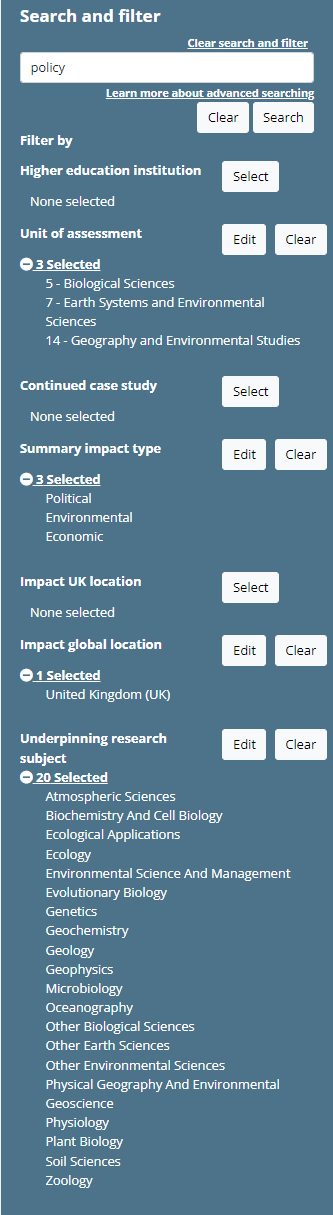

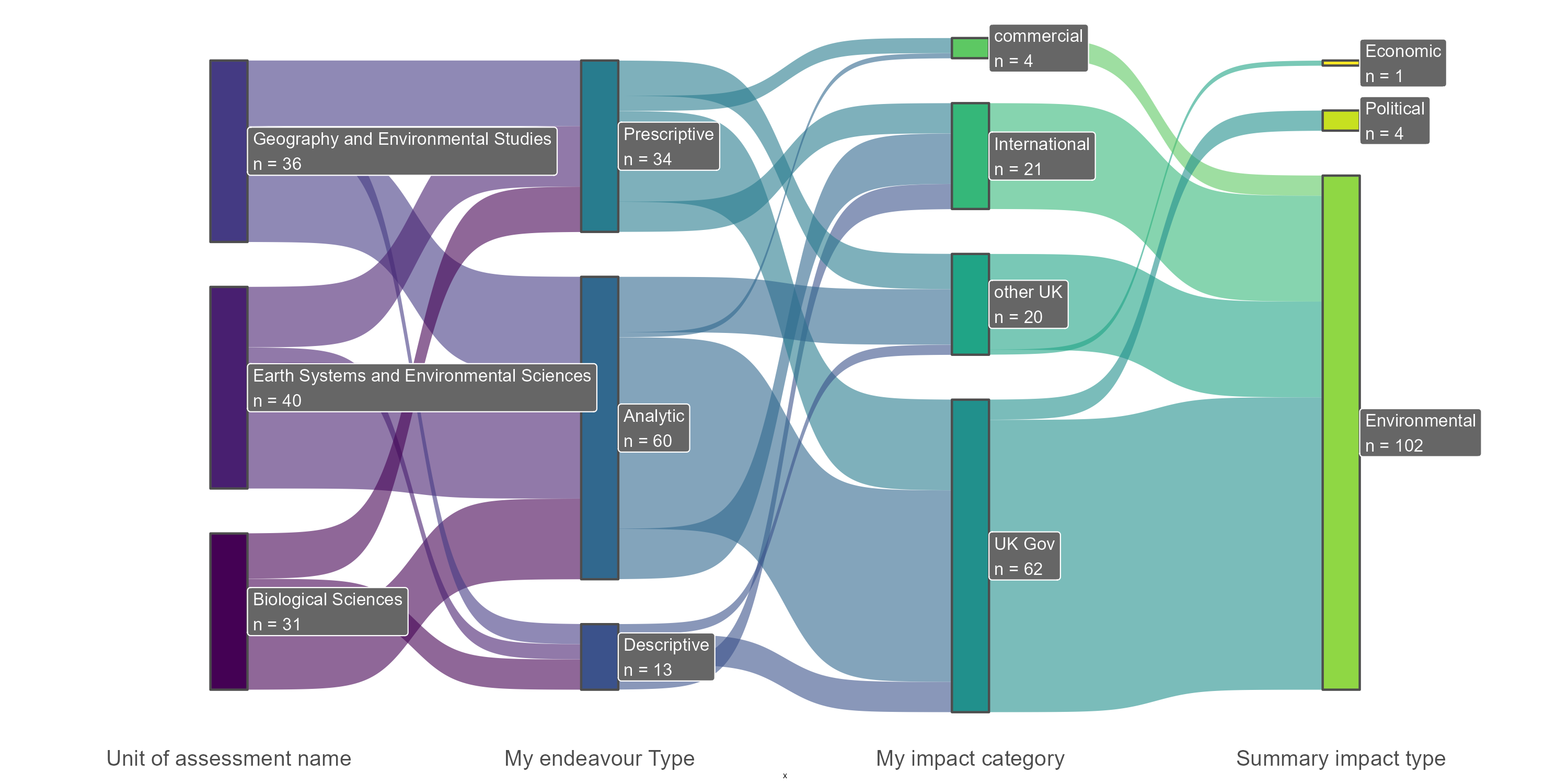

The REF 2021 is a little more promising. I performed a rather rough and ready analysis of the REF 2021 impact case study database to understand if I can use these data to identify scientists who may be able to talk about their work influencing policy. The REF has hundreds of submissions evidencing impact and I was able to search these for the word “policy”, filtering by Unit of assessment, Summary impact type, Impact global location and Underpinning research subject (see Figure 1, left). I then read the Summary impact statement for each of the 107 returned results, and made a rough judgement about the jurisdiction of the impact. If there was any evidence of impact on policy or practice in UK local or national government (including national government agencies), I labelled the example “UK Gov”. If not, I chose an alternative label. This was rather subjective and probably changed as I was labelling - my initial intention was to identify only those cases that impacted the UK Government but as I worked through the examples, I felt that all but the “commercial” examples could be worth investigating further (these categories can be seen in Figure 2).

The REF 2021 is a little more promising. I performed a rather rough and ready analysis of the REF 2021 impact case study database to understand if I can use these data to identify scientists who may be able to talk about their work influencing policy. The REF has hundreds of submissions evidencing impact and I was able to search these for the word “policy”, filtering by Unit of assessment, Summary impact type, Impact global location and Underpinning research subject (see Figure 1, left). I then read the Summary impact statement for each of the 107 returned results, and made a rough judgement about the jurisdiction of the impact. If there was any evidence of impact on policy or practice in UK local or national government (including national government agencies), I labelled the example “UK Gov”. If not, I chose an alternative label. This was rather subjective and probably changed as I was labelling - my initial intention was to identify only those cases that impacted the UK Government but as I worked through the examples, I felt that all but the “commercial” examples could be worth investigating further (these categories can be seen in Figure 2).

I also considered whether the research was descriptive (describing what is), analytic (describing how it is) or prescriptive (defining how it should be to achieve some goal). This was a somewhat limiting exercise because more than one label was often relevant to each research (see quote below) and these labels were difficult to judge from the short summaries which are not always clear about which aspects of the impact arose directly from the research, and which resulted by others taking up that research (and who is to judge these divisions anyway?). However, it allowed further consideration of the research that is deemed to have created impact. Whilst objectivity is often called for from science, the most objective science is arguably descriptive-only and, it seems, such research tends to make less impact - if the lower count of descriptive research in these data (Figure 2) is indicative. This reflects the balance between objectivity/credibility and usability/usefulness (noted in MacKillop et al. (2023) and Wesselink and Hoppe (2020) among others).

Both of the above labelling exercises were initial explorations of the REF 2021 and if such analyses were to underpin my research, I would need to define more clearly what criteria are being used for the labels and, ideally, have one or more independent judge of the labels. Given the limited information in the summaries, it may be necessary to extract the relevant information by further data collection, such as from interview transcripts.

Reading these examples finally gave me a sense of what influencing policy means, in its very wide range of forms. Many of the descriptions were quite high level, but some demonstrated the multiple activities undertaken by scientists. For example, this example (coincidently from UCL, although I didn’t realise until I clipped it for this write-up) describes how:

“IoZ researchers have trained scientists, built research capacity in multiple countries, developed diagnostic tools, and successfully campaigned for the diseases to be listed as notifiable diseases by the OIE World Organization for Animal Health”

Figure 2: The distribution of the 107 extracted examples according to the REF 2021 Unit of assessment name, My judgement of the endeavour type, My [rough and ready] impact category and the REF 2021 Summary impact type

I believe the REF 2021 data provide some good suggestions for research to delve more deeply into and scientists to interview regarding approaches used when influencing policy.

Literature on policy impact

The policy impact measure for the REF 2021 is described in Knowledge Exchange Unit (2021), which is potentially very useful to structuring analysis such as that described above since it lists, for instance, many direct and indirect ways that research impacts policy. Another piece of work that I enjoyed reading about is Kenny et al. (2017). The work studied the role of research in the UK Parliament from the point of view of people using research (the “demand-side”). It provides detailed understanding of what “research” means in the decision-making contexts, as well as indications of why research isn’t always usable. It also suggests that more work is needed in understanding the “supply-side” - it’s always good to have one’s own research justified elsewhere. I think this led to the 3 Thematic Research Leads announced in POST (2022), but I am not sure what else has happened since the publication of the 2017 report.

How to understand how scientists have impacted policy

I have been thinking about my methodologies. In terms of literature, I still have more exploration to do, but have noted some examples that have some detailed descriptions of methods. Dowding (2018) used case studies, surveys and interviews to identify advocacy coalitions. Discourse coalitions professionals interested in policy development (as a field of study rather than the specific policy issues) were identified by Montana and Wilsdon (2021) using semi-structured interviews of those actively engaged in meta-level questions about evidence and policy. Kenny et al. (2017) developed a detailed understanding of the role of research in UK Parliament from a survey, interviews, document analysis, workshop and observation of teams working on specific case studies. And, I don’t know much about ethnography, but I am drawn to the thick descriptions highlighted in Boswell and Smedley (2022)’s meta-ethnography approach.

My sense is that I will perform a document-informed series of interviews. These will draw on documented evidence of policy influence (such as the UKRI or REF 2021 records) to identify and understand the actions of researchers. I need to structure this using suitable frames. There are many to choose from, although most are too broad or non-specific given the limitations of a 3-month research project (I’ve listed below some of the frames that I have found useful for understanding the literature thus far and which may be useful again).

There are three aspects that I consider would be important for structuring my methodology and analysis:

- Determining if structure emerges: If possible, I would first like to derive the discourses, frames or themes that arise out of documents and interviews to understand what, if any, different natural groupings researchers’ perspectives fall into.

- Identifying the actions that influence policy: examples include the actions of policy entrepreneur (PE) and problem broker (PB) useful. For the PE, Cairney (2018) neatly outlined three habits: storytelling, offering a (pre-softened1) solution, and adapting to or adaptation of, the context. It is likely that similar habits can be identified for a PB, perhaps with a well-rehearsed consequences framing replacing the solution habit. These figures, derived apparently from observation, seem to fit with aspects of the roles defined by Rapley and De Meyer (2014) and Gluckman, Bardsley, and Kaiser (2021) for easing scientific knowledge into policy. Thus it may be appropriate to allow for a broader range of figures to be considered in my analysis of the data.

- Identifying the conditions that allow policy to be influenced: The contexts of policy influence are essential to understand, especially given that the PE/PB frame emphasises adaptation (and interpretation if we consider Aukes, Lulofs, and Bressers (2018)). For instance, the type of issue and/or its structure (e.g. Wesselink and Hoppe (2020)) will also be useful to understand. The societal level of governance (local-national-global) may facilitate different categories of influence but may also be suitable for limiting scope (e.g. to national level).

Frames that have been useful

This list is here for my record, I’ve found it useful to refer back to whilst reading literature

- Montana and Wilsdon (2021): Evidence-policy discourses (use these to understand the different perspectives individuals have on how science should affect policy): analysts (evidence based), advocates (better methodologies), applicators (context-specific)

- Wesselink and Hoppe (2020): Problem structure: puzzling v powering — multiple levels in society: macro, meso, boundary organisation, micro — activities for policy problem processing: framing, structuring, knowledge and actor selection, regulating relations between science and policy

- Geuijen et al. (2017): public governance: local, national, global — philosophical traditions: consequentialism, deontological — who determines value: individual, individuals aligned with others, citizens subject to law and governance

- Rapley and De Meyer (2014), Gluckman, Bardsley, and Kaiser (2021): 5 roles: pure scientist, science arbiter, science communicator, honest broker, issue advocate

- Aukes, Lulofs, and Bressers (2018): interpretative framing: sensemaking, defining problems in others’ terms, building epistemic communities, willing to take risks

- Mintrom (2019): attributes, skills and strategies of policy entrepreneurs

- Piddington, MacKillop, and Downe (2024): 4 profiles of policy-makers in terms of their views on what is evidence

- Cairney (2018): 3 habits of PE: storytelling, pre-softened solution, adapt and adapt to context to create and exploit opportunities

- Karlsson and Gilek (2020): framework of concepts used to explain science-policy gap from across disciplines:

- Wesselink and Hoppe (2020): academic endeavours are: descriptive (“what is actually happening”), analytical (“how can we understand what is happening”), prescriptive (“how can we improve the situation”)

- Olejniczak et al. (2019): policy design work into: Establishing what solutions work, Explaining why solutions work (or not), Transferring research findings into policy actions

- Kerschner and Ehlers (2016): categories of attitudes to technology: Enthusiasm, Determinism, Romanticism, Scepticism

- Holling and Gunderson (2002): adaptive cycle phases: exploitation, conservation, creative destruction, renewal

- Geels (2004): multi-level perspective

TL;DR I’m starting to hone in on whom and how but need better structure for analysis

Using the REF 2021 and potential UKRI Gateway to Research, I may be able to interview a range of research and researchers to study in more detail. I am also gaining a sense of what may be meaningful in terms of actions and contexts but need to refine this more - possibly by performing more data analysis.

References

Ewert Aukes, Kris Lulofs, and Hans Bressers. “Framing mechanisms: the interpretive policy entrepreneur’s toolbox”. In: Critical Policy Studies 12.4 (2018), pp. 406–427. 10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219.

John Boswell and Stuart Smedley. “The Potential of Meta-ethnography in the Study of Public Administration: A Worked Example on Social Security Encounters in Advanced Liberal Democracies”. In: Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 33.4 (Oct. 25, 2022), pp. 593–605. issn: 1053-1858. 10.1093/jopart/muac046. https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-pdf/33/4/593/56797599/muac046.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muac046.

Paul Cairney. “Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs”. In: Policy & Politics 46.2 (Apr. 16, 2018), pp. 199–215. 10.1332/030557318X15230056771696. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/pp/46/2/article-p199.xml.

Kris De Meyer, Emily Coren, et al. “Transforming the stories we tell about climate change: from ‘issue’ to ‘action’”. In: Environmental Research Letters 16.1 (Dec. 23, 2020). 10.1088/1748-9326/abcd5a. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abcd5a.

Kris De Meyer, Lucy Hubble-Rose, et al. Net Zero Innovation Programme: Seven Insights to Manage the Complex Nature of Climate Action Delivery. 2022. [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/climate-action-unit/sites/climate_action_unit/files/seven_insights_-summary_and_where_to_find_more.pdf](https://www.ucl.ac.uk/climate-action-unit/sites/climate_action_unit/files/seven_insights-_summary_and_where_to_find_more.pdf).

Keith Dowding. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework”. In: Handbook on Policy, Process and Governing. Dec. 28, 2018. Chap. 13, pp. 220–231. 10.4337/9781784714871.00020. https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/edcoll/9781784714864/9781784714864.00020.xml

Frank W. Geels. “From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory”. In: Research Policy 33.6 (2004), pp. 897–920. issn: 0048-7333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733304000496.

Karin Geuijen et al. “Creating public value in global wicked problems”. In: Public Management Review 19.5 (2017), pp. 621–639. 10.1080/14719037.2016.1192163. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1192163.

Peter D. Gluckman, Anne Bardsley, and Matthias Kaiser. “Brokerage at the science–policy interface: from conceptual framework to practical guidance”. In: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8.84 (1 Mar. 19, 2021). 10.1057/s41599-021-00756-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-021-00756-3.

C. S. Holling and Lance H. Gunderson. “Resilience and Adaptive Cycles”. In: Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Ed. by Lance H. Gunderson and C. S. Holling. 2002. Chap. 2. https://www.loisellelab.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Holling-Gundersen-2002-Resilience-and-Adaptive-Cycles.pdf.

Mikael Karlsson and Michael Gilek. “Mind the gap: Coping with delay in environmental governance”. In: Ambio 49.5 (2020), pp. 1067–1075. issn: 00447447, 16547209. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48727222 (visited on 04/29/2024).

Caroline Kenny et al. The Role of Research in the UK Parliament. Volume one. Houses of Parliament, Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology, 2017. https://post.parliament.uk/the-role-of-research-in-the-uk-parliament/ (visited on 05/22/2024).

Christian Kerschner and Melf-Hinrich Ehlers. “A framework of attitudes towards technology in theory and practice”. In: Ecological Economics 126 (2016), pp. 139–151. issn: 0921-8009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.010. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800916302129.

Knowledge Exchange Unit. Research impact on policy. Briefing. UK Parliament, June 2021. https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/assets/teams/post/research_impact_on_policy_briefing_document_june21.pdf

John W. Kingdon. “How do issues get on public policy agendas?” In: Sociology and the Public Agenda. Vol. 8. 1. 1993. Chap. 3, pp. 40–53. 10.4135/9781483325484. https://sk.sagepub.com/books/sociology-and-the-public-agenda/n3.xml.

̊Asa Knagg ̊ard. “The Multiple Streams Framework and the problem broker”. In: European Journal of Political Research 54.3 (Apr. 27, 2015), pp. 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12097. https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1475-6765.12097.

Eleanor MacKillop et al. “Making sense of knowledge-brokering organisations: boundary organisations or policy entrepreneurs?” In: Science and Public Policy 50.6 (2023), pp. 950–960. issn: 0302-3427. 10.1093/scipol/scad029. https://academic.oup.com/spp/article-pdf/50/6/950/54252849/scad029.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad029.

Michael Mintrom. “So you want to be a policy entrepreneur?” In: Policy Design and Practice 2.4 (Oct. 14, 2019), pp. 307–323. 10.1080/25741292.2019.1675989. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2019.1675989. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2019.1675989.

Jasper Montana and James Wilsdon. “Analysts, advocates and applicators: three discourse coalitions of UK evidence and policy”. In: evidence & Policy 18 (3 Feb. 16, 2021), pp. 456–472. 10.1332/174426421X16112601473449. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/evp/18/3/article-p456.xml.

Karol Olejniczak et al. “Policy labs: the next frontier of policy design and evaluation?” In: Policy & Politics 48 (1 Sept. 4, 2019), pp. 89–110. 10.1332/030557319X15579230420108. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/pp/48/1/article-p89.xml.

Grace Piddington, Eleanor MacKillop, and James Downe. “Do policy actors have different views of what constitutes evidence in policymaking?” In: Policy & Politics 52.2 (2024), pp. 239–258. 10.1332/03055736Y2024D000000032. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/pp/52/2/article-p239.xml.

POST. POST launches new research collaboration with academics based in Parliament. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Nov. 21, 2022. https://post.parliament.uk/post-launches-new-research-collaboration-with-academics-based-in-parliament/.

Chris Rapley and Kris De Meyer. “Climate Science Reconsidered”. In: Nature Climate Change 4 (Sept. 2014), pp. 745–746. https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2352.

Anna Wesselink and Robert Hoppe. Boundary Organizations: Intermediaries in Science–Policy Interactions. Oxford University Press, Aug. 27, 2020. 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1412. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1412.

Cairney (2018) identified pre-softening as part of the adaptation habit, but it fits neatly into the solution habit ↩

Comments powered by Disqus.